- Home

- Rosie O'Donnell

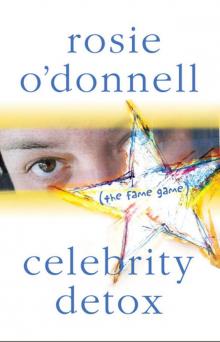

Celebrity Detox

Celebrity Detox Read online

Copyright © 2007 by KidRo Productions, Inc.

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

The Warner Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: October 2007

ISBN: 978-0-446-19993-3

Contents

Copyright

1. The Two Bs

2. Fame Is Like a Tattoo

3. King Midas and Me

4. Barbara’s Show

5. $$$$$

6. Letter to My Brother

7. Who’s Real?

8. Talking about Barbra

9. The Sound of Color

10. Trumped

11. Thank You for the Show

12. You Know Where I Am

13. Two Faces

14. The Fame Game

To my mother and yours.

Thanks to:

Lauren Slater

Jamie Raab

Ed O’Donnell

Michele Riordan Read

Vivian Polak

Nan-jo

CHAPTER 1

The Two Bs

My mother loved Barbra Streisand. A lot. She had all her records, plus she watched her whenever she did a talk show or had a TV special. My mother listened to Funny Girl on the blue Victrola cabinet she got at the flea market, a cabinet she stripped and stained herself somehow, alone in the garage. My mom had five kids and her own mother living with her. How did she have time to do anything? I have four kids, a wife, and two nannies, and I am often overwhelmed.

My mother took the time out to fill up on yellow. Yellow is my shorthand for real, for true, for beauty. Yellow means what is good with our world. My mother knew yellow. We watched Billie Jean King together as she beat Bobby Riggs. My mother took us to Radio City to see the Christmas show. My mother pointed out the women who had risen above what it meant to be a woman, back then in the 1960s, and even now too. “Streisand,” my mother would say, “look at her, from Brooklyn, look at her now.”

“Anything is possible, little girl.” My mother told me this, in her own way, usually without words. Irish people are sometimes not so good with words. They are sometimes not so good with feelings. That’s why inside I’m a Jew. I want to feel it, talk it, live it, scream it. I want it all out there.

At some point in my childhood, my mother told me about Barbara Walters. Probably she pointed her out to me on the TV. This woman was a weather girl who worked her way up to being co-anchor with Harry Reasoner, who interviewed every world leader, and she did all this at a time when women were told it was impossible. She paved the way for Oprah and Katie Couric and Diane Sawyer and every TV newswoman, every female TV personality for that matter. My mother recognized Barbara Walters’s meaning from the get-go.

We used to watch Barbara Walters. My mother recognized that Walters was always imparting two levels of information, the spoken and the implicit. The spoken was the this and that of the day’s news. The implicit was that it was now possible for a woman to deliver that news. We watched Barbara Walters’s phenomenal rise to the top. We watched, more closely still, the wide wake she left, a path I think my mother wanted me to see. Barbra Streisand, she was about the ultimate; she was genius incarnate. She was a goddess to us, while Walters was of this world. What Barbara Walters proved to us was that women could rise in this world. What Barbra Streisand proved to us was that art was beyond gender, and through it one could rise right beyond this world, and get to someplace better.

Several years ago I left my show. I’d lost the ability to get to the place Streisand had shown me was possible. Six years of celebrity-hood had left me depleted, and I had to find myself, find my art, and find my family again. I went off the air so I could touch down on the ground. And I did. And the ground felt good. I had my kids back—Chelsea, Parker, Blake, and Vivi. I had my wife. Kel and I had started up a gay cruise ship business and twice a year we went sailing with other gay families. We filmed it all and made a documentary of what it means to be a gay family. We screened the documentary one night at the New York Arts Center. This was in April 2006. One month prior to this, March 17, had been the thirty-third anniversary of my mother’s death. There were rumors, sometime around then, that Streisand was thinking, at age sixty-four, of going back on tour. It was April in New York City, the trees were putting on green sleeves, boats were back on the Hudson, and my movie was finally done.

And so Barbara Walters came to this first screening. She wasn’t a stranger to me. Not only had I spent much of my childhood watching her on TV and, more significant still, watching my mother watch her on TV, I’d also known her as an adult, in my own right. I’d had dinner with Barbara Walters, and she’d even been to our home to interview Kelli once. We were friends in the celebrity kind of way—you know and respect each other—you have dinner every few months. You don’t chat on the phone, but there is an undeniable association, a shared intimacy that paradoxically lacks all intimacy. You are members of an exclusive club where everyone speaks a language very few others have been able to attain. Fame.

A few weeks before the premiere of my documentary, I’d been to a party at Barbara’s house. This was a party for Mike Bloomberg, and Kel got all dressed up to go. Kel looked beautiful. She always does. I was wearing my standard black pants from Target and my J. Jill clogs, and we went uptown, and we were curious. We’d never seen Barbara Walters’s house before. Going there was a fairly big deal. We rode the elevator up and walked into a stunning red room, and there was Barbara, in the center, wearing a beautiful gold lamé evening gown, the same one she probably wore to interview some heads of state. Maybe Idi Amin Dada or Prince Charles or even the Dalai Lama. She looked flawless and stunning in her bright red room, a Julian Schnabel painting on the wall, a double piano, the keys as white as teeth, a man in a tux playing. I was, well, I was enchanted, almost flabbergasted—the color, the beauty, the women with their silk sheaths and the hors d’oeuvres served on trays with scalloped rims. A lot of people might assume that’s what celebrities do, go to fancy parties with double baby grands in merlot-colored rooms, but the fact is, I don’t. Mostly, especially since leaving my show, I’m home with Kel and the kids, eating string-bean casseroles with fried onions on top, Blake’s favorite. I remember a waiter whisked by, offering me some flaky layered thing.

At dinner I sat next to Liz Smith. I think it was during the serving of the second course that in walked this woman, gorgeous, I mean, she looked like Ann-Margret meets Jessica Rabbit. She had a Clinton-like charisma. When I asked, “Who the hell is that?” Liz Smith said, “That’s Georgette Mosbacher.” Georgette looked at me from across the room. She seemed dreamlike. I said to Barbara Walters, “I have to know her.” Barbara may not have taken me seriously at first. “Look, Barbara,” I kept saying, “I’m enchanted.” I don’t know if Barbara arranged it or not, but not long after Georgette came over to me. She leaned in real close and said, “I’m a Republican, don’t tell anyone. I’m in the closet!”

People have questioned me about the way I’m drawn to certain people, men and women both. My attractions to other people are not sexual in any sense. That seems hard for people to really believe. There was, for instance, a weekend when Jane Fonda came to visit me. We were in my craft room. I was showing her some art I had made. In one of my collages was a photograph of Madonna. “You two were love

rs?” Jane Fonda said, more of a statement than a question. I said, “No, we were never ever lovers. We were sisters from the moment we met.” There was never anything sexual about it. This surprised Jane. Her surprise surprised me.

After dinner the night of Barbara’s party, I remember singing “Liza With a ‘Z’” as a beautiful old-school pianist played on the baby grand. I could feel Barbara Walters watching me. Sometimes that happens. A stare seems to have weight, or touch. Someone’s eyes land on you. That night it was Barbara’s eyes, mixed up with my voice, as I sang “Liza With a ‘Z.’” I was in Barbara’s world, and the song was a string pulling her back, I think, to the days when she was younger, when her father, Lou Walters, who owned the famous Latin Quarter nightclub, was alive. I believe that song brought her back to something in her past, and I could see her seeing me, Barbara Walters, the woman my mother admired for the wide wake she made, the woman who, in delivering news, became news herself.

I am drawn to many people in many different ways—sister, friend, buddy, colleague—but to Barbara, I was drawn differently. Perhaps because my mother died when I was still a child, I will forever in certain instances see women who are much older than I am as a child might. Barbara was the age my mother would have been had she survived her cancer. And I also knew Barbara had a daughter, and was therefore a mother. When I saw Barbara, I saw my mother seeing her; I saw the television in our house on Rhonda Lane, and the gray telephone poles supporting miles and miles of wires stretching high up a hill, toward a place we could never get to.

Maybe the song was bringing Barbara back to her past; all I knew was at that moment we shared something real. I wondered what it was. And then the song ended. It was time to go home. We left the red room, and during the many many months I worked on The View I was not invited back.

But the room left an impression on me, so much so that even now, if I close my eyes, I can see still its hue, a red that resists words but that pulses on nevertheless, a color too rich, too much, like the woman herself; she is striking and beautiful, but also blinding, Barbara Walters, her beautiful red giving off a glare that makes one want to wince, in both pleasure and pain, and then to turn toward something softer.

Two weeks after the red room, the party, I invited Barbara Walters to the premiere of my documentary, and I’m glad I did it. I’m proud of that film. It shows gay families as they really are, struggling with all the same things every other family struggles with: sunscreen, diapers, sippy cups, and stubbornness. What makes the film so moving is how grateful the families are to finally have a place, some place, to go together. I’m also proud to have made it at a time when my career was down in the dumps because here I was doing something, creating a whole other thing. There was beauty and truth in that movie, a film about children and parents, about love and human equality and vulnerability. The women who directed it get all the credit. I’m not sure I could have put it together and said so succinctly what it is that gay families are about without their help. The movie ends with a view of the huge ship on the Caribbean blue waters.

And then the lights went back on and people rustled up out of their seats. I was in the lobby and I saw Barbara Walters come out of the theater, crying. “Rosie,” she said, “would you ever consider being the permanent co-host of The View?”

I looked her in the eyes. That she was moved moved me. That she had shown working-class women like my mother that a wider wake was possible—that moved me too. I’d been out of show business for four years, a sacred silence this had been, but maybe I was ready to go back. What happened next I didn’t plan. I certainly could never have anticipated it and still today I can’t explain it. All I know is this. “Barbara Walters,” I said. “I’ll do whatever you ask.”

As it turns out, I did not do whatever she asked. I came on The View, and this is the story of how it all happened, offstage, onstage, how we struggled to make the show, and then so much more than that. This is an account of what it means to make a show, and a friend, and an enemy, or two. This is about where we went wrong, and right. It’s a story about stars and celebrities and one woman—me—going off air four years ago and then trying to reenter orbit, not knowing if she can. It’s the story of wondering whether I could give up the addictive elixir of fame and then go back, wondering if it’s possible to sip instead of slug. It’s a revision of a book I did four years ago, just as I left my show, but trashed because it was too soon. I could go on and on, it’s a story about so much, but the only thing that matters here, now, is her question, “Will you come?” and my response, “I’ll do whatever you ask,” and how over the year that turned out not to be true at all, how I did not do whatever Barbara Walters asked, how in fact I did very little of what she asked, how she started as a sort of mother, and me a child willing to obey, and where we finally ended up, months later, two very different women with very different values, living in very different rooms, battered by betrayal but nevertheless doing what women all over the world do best. Barbara Walters and I, after all that happened over those hard months, after all the Trump dump and divisive ways of the world we are in, we have still, and nevertheless, at the very end, we have found a way to talk. We have found, dare I say, a way to love? We found, I have to hope, a friendship that, like any other friendship, is both compromised and connected.

CHAPTER 2

Fame Is Like a Tattoo

Q&A with Lauren Slater

LAUREN: So, you’ve been off the air for how long now?

ROSIE: Four years?

L: And if you had to sum up in a nutshell why you left—

R: Losing touch.

L: Right, you’ve said this before. You keep saying you feel celebrities need a rehab where they go to detox from fame. Because they’re so out of touch they haven’t learned the normal activities of life. Like never learning to parallel park.

R: Well, I’m not saying you never learn, I just think that when you’re very famous, as I was, there are things you don’t have to do that someone else will do for you, and you will allow them to do them. And the sad thing is, you get to the point where you basically allow others to live your life for you. I mean, that’s the bottom line. You’re going out to entertain strangers while someone else is home raising your kids and it just feels like an absurd choice. Listen, I had six years of mainlining stardom and I left because I wanted to try something else. Being that famous becomes absurd, you’re in high waves.

L: You don’t realize how high the waves are until—

R: Until you try to make it back to shore. When you walk through a mall you hear people whispering your name. You’re constantly hearing, “There’s Rosie O’Donnell.” What you have to do is shut out the noise, and in order to do that you have to start shutting out other things too and eventually it distracts you from your own spiritual journey.

L: So you want to do a book about why you left your show. Because, as you say, you feel you were mainlining stardom. You feel you almost, or actually did, get addicted. And over the past years, off the air, you’ve been, I guess, detoxing, and seeing what happens when you’re not on screen anymore, when no one pays any attention to you anymore, when you have time to be with, and rediscover, your kids. Have you, in fact, detoxed?

R: Yes, I think I have. Now mind you, I have nannies . . . I have a wife, and two nannies. There are always at least three women raising four children in my house. It takes a village, I made a village of women to raise these four children. I have it easy—very easy; with fame comes wealth—help, access, and freedom. But I’m still the kid I was. Only everything’s easier, cleaner, and better and I’m not looking at the world through the prism of a victim anymore.

Basically, I left my show in order to come back and feel the small moments as huge. You start to miss the small moments, the real parts of your life. You miss the kids’ stitches and the soccer games and the first steps. Yes, I left in order to come back.

L: What are some of the skills you learned since you’ve left?

R: Parkin

g the car. Just driving myself, I had had a driver for six years. My goal that first year off TV was to pick up my kids at school every day. In order to get a parking space, I showed up a half hour early every day. And that’s how I met my friend Sharon. She too was early every day for pickup. She’s very intense in a way that felt familiar. We bonded. She helped me with my reentry into the world. She saved me seats at the Christmas concert, reminded me which day I had to bring a snack. We went to the mall, to the sale days at A.C. Moore. Crafty Sharon, she helped me a lot. She helped me relearn some of the basic things in life.

L: Do you think you’ll ever go back on air?

R: No. The gross excess of the whole thing, it became repulsive to me. My perspective got skewed. Now, mind you, there are times when it came in very handy.

But listen, fame is like a tattoo. It never goes away. Eddie Munster, Butch Patrick, now fiftysomething—he was at a diner trying to get a cheeseburger and the waitress said, “Oh my God, are you Eddie Munster?” He can’t get rid of that. It’s a tattoo on him forever. I used to think the only way to get unfamous was to pull a Garbo and literally disappear and stop speaking to anyone publicly and go out in disguise. I used to think I’d never be unfamous in America because that show was too big for too long. Maybe no matter what I’d always be identifiable. Anyway, as for going back on air, that’s not where I’m at right now.

L: So where are you at?

R: Home. I am home. Still doing foundation work. I’m opening a musical theater school in Manhattan. I’d like to get, like, ten rich feminists together. And each of us could give a million dollars. We could fund a feminist majority. It’s such a patriarchy and we’re so oppressed; we’re raped as entertainment. On network TV. Terror—right here in the USA. Where are the women leaders? Shirley Chisholm—Gloria Steinem—Betty Friedan. It makes me sad. We seem to be going backward as a nation. So, I want to get the rich women in this country together, to start something by and for women and girls. It seems so simple to me, so obvious. So why doesn’t it happen?

Celebrity Detox

Celebrity Detox